Think of all the media you enjoy. Games. Movies. Television. Novels. Most of them probably have a story. If you get a bit more technical, those stories all take place somewhere. Literature teachers would call that the setting. I think of that place as a “world” for each piece of creative work. So worldbuilding is really just the process of making those worlds. Your desires, your imagination, and your knowledge are your only real constraints in worldbuilding. Admittedly it can get overwhelming—there’s a lot to learn, a lot to do, and many ways to get it done. Fortunately I can give some pointers on how to get started! Fair warning though: the tips in this short article amount to just the… tip of the iceberg when it comes to worldbuilding methods. So whether you’re new to the concept or maybe just searching for a different perspective, here’s my intro guide to worldbuilding.

Genre and Platform

From my experience, the most difficult worldbuilding hurdles often lie at the very beginning.

But once you get over the starting line you’re free to enjoy the journey.

And for many people, worldbuilding can be an enjoyable effort that takes months or even years.

Before I get started worldbuilding for a project, I commit to two aspects that will focus my worldbuilding.

The first aspect is genre and the second is platform. Let’s cover genre first, specifically literary genres.

Genres are categories for works that have similar content, form, and style. For example, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, and A Song of Ice and Fire fall under the fantasy genre.

You may already know others off the top of your head but here are a few more that might sound familiar: science fiction, horror, action, western, historical—and more!

Choosing a genre for your world greatly benefits you in building it up. Firstly, it helps you identify possible sources of inspiration and research since you can refer to other works within the genre.

Secondly the genres provide a reliable set of criteria for style, tone, and even aesthetics. Criteria will inform your worldbuilding and keep your designs consistent within the genre(and consequently consistent within your world).

Consistency is vital to making your world make sense to you and your audience.

For example, a reader would scratch their head at the presence of light speed-traveling spaceships and photon blasters in a traditional old western setting(think along the lines of desert towns with tumbleweeds, cowboys galloping on horses, and gunslinging marshals).

How hard you commit your world to a genre may change as you worldbuild more and more.

Your world might even take on the qualities of other genres as you get more ideas! But while you’re still getting started with worldbuilding, try to focus your ideas within a genre. This prevents you from being too overwhelmed by all the possibilities.

Now the second aspect is the platform, also known as the medium.

The platform is how you want to present your worldbuilding.

Mediums include novels, short stories, screenplays, visual arts, board games, video games, and a lot more (from physical to digital media).

How you present a world determines what parts you want to develop and emphasize, so it’s better to keep it in mind sooner rather than later.

For example, video games will include a lot of visual cues in the game world because players could potentially directly interact with them during play. On the other hand, novels give authors leeway with writing longer passages to describe locations, dialogue, and characterization.

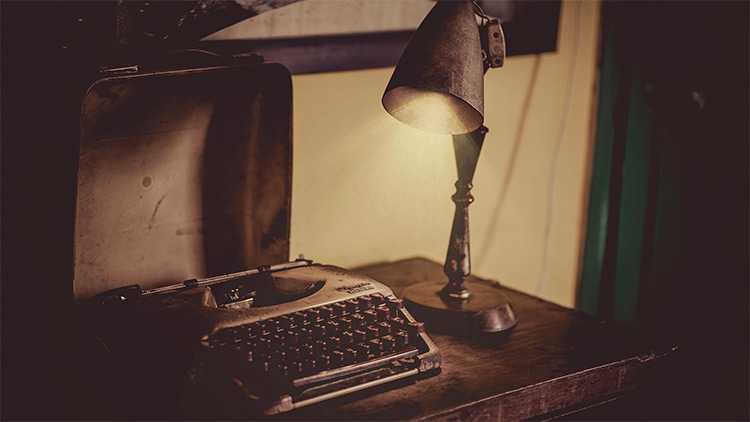

Just a short aside here: I think the easiest way to record worldbuilding ideas is to write or type ideas.

This may be different from your preferred medium if you don’t want to present your world in the written form.

But when you write to record, it can be anything from paragraph to bullet points. I know artists may prefer doing sketches or concept art. However you want a reliable record of your world and the ideas that you want to work on, and I’ve found that text is the fastest way to move forward.

Getting Started

Once you have the genre and the platform sorted out, you have a good basis for worldbuilding. Next you get actually make stuff up. Yeah, you read that right. The core of creating any fictional work is making stuff up, and the worldbuilding process is the same at heart—except it spans an entire world now. Trying to think of everything at the start may seem overwhelming. And it’s alright to feel that way. The best advice I can give is this: you don’t have to create everything. At least not all at the beginning. Start off with an idea. Just one. Fortunately, there are different ways to tackle this part…

Starting Small

I personally like to “start small” by thinking up smaller, vital parts of my world. Then I build up my world by putting those parts together. For example, characters can give a strong foundation for worldbuilding. Think of it this way: you live your life every day and experience the real world as a person. Made-up people in a made-up world follow the same concept. Where people live, what they do, and how they got to where they are offer fantastic ways to build up the world around them. If making people up doesn’t appeal to you then try creating other parts of the world. Maybe you want to create a cool place like a city. Maybe you enjoy history, so maybe you’ll prefer detailing historical events like the causes and consequences of a famous battle that happened in your world. If you love animals, make up an awesome new creature. Flying bear-giraffe hybrid? That sounds both terrifying and fantastic! The key with starting small is that you get to create individual pieces of the world first. Even the most mundane parts of our reality have a story behind them. A computer didn’t always exist, and a lot of effort goes into making one that I could use to type worldbuilding articles on. Worlds you create will parallel those situations. Breaking it all down to explain how it happens is the core of worldbuilding. Then, like putting together a massive jigsaw puzzle, each piece builds up to a bigger picture!

From the Top

Another approach is a thinking exercise that begins at the metaphorical top of the world. Whether you want to create one planet or an entire universe, you determine the upper bounds for the scale of your worldbuilding. While making stuff up, knowing the setting’s physical limits helps you focus on what you want to create. Envision what you want your world to look like if you were looking at it from space. What’s the shape? Round? A ring? Flat? What does the surface look like? Covered mainly in water with some continents like Earth? All green and leafy like a massive rainforest? Or barren like the Mojave Desert after a nuclear apocalypse? After that, start filling in the world with smaller and smaller details. You can explain why the planet is covered in water, or maybe why it has no water at all. Or pick one of the continents and describe it. Maybe there are beasts that only exist in that part of the world, so create those. Like a Russian Matryoshka doll, there’s always something else inside that you can build. At this point the worldbuilding process comes full circle back to the “starting small” method. The bottom line either way is that you create what you want to in your world. It could be to help explain why it is what it is, or maybe you just want to create something awesome that fits into the world. The main difference here is how you got started, but I can guarantee that there’s an infinite number of things you can still make up even whether you start “small” or “from the top.”

Finding Inspiration

No matter how you worldbuild, it’s not unusual to somehow feel like you have no good ideas. Don’t be ashamed of that since you wouldn’t be the first nor the last. It helps to know that it’s not always because you have no ideas. We’re constantly thinking! The difficulties really lie in creating something that seems unique to your world. For that problem, my classic solution is to find some inspiration. And what’s the easiest way to do that? Well, just look back at the genre you chose for your world. Refer to other works in that genre, then see what concepts you like or find interesting. However you don’t want to just steal ideas. At worse, you’d commit plagiarism; at best, what you’re making won’t really feel like unique—it wouldn’t be unique content that you made. Instead, figure out what you liked about those ideas. Then we get to the part that takes the most effort: finding a way to add your own spin to an idea in a way that fits your world. No matter how you managed to get your ideas, the key is to make them yours. Perhaps you add a refreshing twist, or you break down a concept and rebuild it almost completely differently. Up to you. From there build up your world with these ideas that you have made your own. Focus on the parts that most interest you. Create other parts of your world as they become relevant to you. When you’re still starting don’t get too bogged down by details to the point that you stop creating. Only you will know what parts of your world are truly important, and understanding what matters will keep you worldbuilding reliably.

Putting It All Into Practice

Let’s wrap up with an example… let’s say I hypothetically have a world in the fantasy genre that I want to use as a setting for a book. I’m not too interested in the bigger picture with planets and landmasses and stuff. However, I want to focus on the people living in my world. And I think it’d be cool if they could use magic in their everyday lives. There’s a lot to unpack there now. But my first question is “How?” I enjoyed how wizards worked in Harry Potter so I look a bit more into how J.K. Rowling handled magic in her books. Most of her wizards used a wand, but sometimes they didn’t need it to use magic. Now I really like how they could verbally say spells that activated magic, but I think the whole wand-waving thing is a bit silly and will be excluded from my magic system. I also want certain types of magic to be more special or harder to come by in my world too. So I’ll brainstorm a bit more. I look to other fantasy works that have magic, and I briefly remember Disney’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice from almost a decade ago. Now I decide that people aren’t born just using magic in my world. They need to learn how to chant spells, but I don’t want to have a Hogwarts rip-off. Instead the people in my world learn spells from specific teachers through apprenticeships, similar to the movie. And I’ll add a twist: two people need to have compatible magical wavelengths for a student to learn from a teacher. Wavelengths are almost like magical blood types, which is another cool aspect of my world I can build up later. After that, apprenticeships could take years to complete for students and the whole process requires a lot of energy and time investment from teachers. All those details give me the basis for how magic works in my world, and that will be pretty important because it affects everyone living in it. I can then consider making up characters that would be teachers or students, and I foresee having to create more details to build up their realities. And so on. My example demonstrates only one iteration—my iteration of the worldbuilding process where I borrowed from both the “starting small” and “from the top” approaches. As a creator you have the freedom to experiment with different ideas in a way that’s best for you. And much like most creative arts, there are very few rules if the outcome is good. You can start where you want, keep what you love, change what doesn’t work, or just toss out what you really don’t like. There may always be something more but that’s a good thing. A lot of the fun and thrill in worldbuilding comes from making the world you want that fits the story you tell. Lastly, have fun! Enjoying what you make will help a lot keep you excited about worldbuilding.